Microfinance Can Change the World

We are claiming April as the month of Microfinance.

All are welcome to join our community: microfinance professionals, researchers, and enthusiasts; chief executive officers and loan officers; small, medium and large-scale microfinance institutions; microfinance institutions that operate in Bangladesh, Bolivia, Pakistan, South Africa, the United States…anywhere. Voices from the mainstream and voices of dissent are welcome. Diversity in our community will be accompanied by a diversity of experiences, beliefs, and narratives regarding microfinance.

Resources

What is Microfinance

Impact

Success Stories

News

About Month of Microfinance

We have a lot of questions. Some are expansive: When does the pursuit of scale come at the expense of clients? Does microfinance help move clients out of poverty? Others are specific: What is a fair interest rate to charge? Which fees are consistent with client-centered microfinance? Answers are good. But, conversation – nuanced conversation – that allows for ambiguities and explores the tensions at the heart of client-centered microfinance is even better.

Our Partners

To support our initiatives you can order custom stickers from our partner. The proceeds help with microfinance initiatives. Whether you need 50 custom stickers or 1000, you support matters. If you want to try before you order, you can get free sticker samples.

Read the Latest

REFLECTIONS ON STARTING MICROFINANCE IN A NEW COUNTRY: BRAC’S JOURNEY IN MYANMAR

In 2014 BRAC launched its microfinance operations in Myanmar – one of the last countries in the world to open up its economy and simultaneously the country with one of the poorest and most unbanked populations. Within three years BRAC has grown to serve over 40,000 women. Read about its journey in a country full of opportunities and challenges.

BRAC comes to Myanmar

Since 2010, Myanmar has been undergoing a series of political and economic reforms; experiencing rapid economic growth as a result. BRAC decided to come to Myanmar at a time when Myanmar’s nascent microfinance (MF) sector was seeing early growth, with a handful of international and local NGOs starting to focus on financial inclusion. A FinScope survey in May 2013 showed that less than 5 percent of Myanmar’s adults had a bank account. The supply of financial services for micro and small businesses reached less than 10 percent of potential customers leaving most of Myanmar’s demand for credit unmet. This was in part because many of the existing microfinance providers were yet to balance sustainability with broad outreach.

BRAC launched its microfinance operations in Myanmar in 2014 as a financially sustainable company. Consequently, all operations had to be self-financed as we could not rely on grants, demanding us to be as business-minded as possible in achieving our social mission of financial inclusion of the poor. BRAC’s general focus for microloans and voluntary savings products is poor women from mostly rural areas involved in various income-generating activities.

Changing financial lives client by client

One of the women BRAC works with is Daw Zar Oo. She might not be the typical entrepreneur but has managed to change her life around and ease some of the financial stress that previously occupied the minds of her and her husband. Daw Zar Oo is operating a small grocery shop, a small-scale broom production as well as paddy farming in the village Koot Kone in Oaktwin Township. Like many people in Myanmar, she is trying to sustain a living in a rural area, with limited infrastructure and beyond the reach of the more profitable markets of the larger cities in central Myanmar. Unlike many other rice farmers, Daw Zar Oo can afford not to sell her rice directly after harvest, when prices are lowest. Instead, she stores the rice in a traditional container made out of bamboo and cow dung and sells it during the year once prices are higher. Going from incredibly high informal loans from loan sharks, Daw Zar Oo was happy to discover the possibility of joining a microfinance group with her friends and neighbors, through BRAC. Perhaps on the face of it seems like a minor change, borrowing the loan from BRAC has enabled Daw Zar Oo to buy stock for her store. This is helping her to prepare for business throughout the different seasons of Myanmar, instead of relying only on the Monsoon and Summer paddy as is very common for the typical Myanmar farmer. BRAC’s loan also enables Daw Zar Oo to smooth income and consumption over the year and create some breathing room for the family to see the market potential in their own surroundings.

Overcoming challenges by applying institutional learning

From the start, BRAC benefited enormously from the years of experience and learning acquired from its operations in seven countries across Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, enabling it to adjust best practices to the Myanmar-specific context. Naturally, there have been some minor and major challenges and operational constraints along the journey. In the first years, Myanmar witnessed political instability and in more recent times ethnic and religious tensions. While access to finance is very limited throughout Myanmar, microfinance as a tool for development does not suitably serve those living in displacement and in areas with ongoing conflict. Mindful of this, BRAC is learning how our vast experiences from humanitarian disasters; in water, sanitation and hygiene; and administering community health programs can be applied as BRAC gets to know the different areas of Myanmar better. For now, the microfinance program which is collateral free and in a group loan modality, demands a certain level of stability to assist small entrepreneurs like Daw Zar Oo to sell her produce and groceries. We have also learned to take an organic approach to expansion, whereby the program tests the ground from one village to the next before laying down roots. Hereby, we take an incremental yet overall more efficient approach to growth as compared to countries where we decided to open offices in a sporadic way and in remote places from the very beginning.

Myanmar also lacks infrastructure, clarity on immigration rules, restricted mobility and limited skilled human resources. All these factors pose operational constraints for microfinance institutions and NGOs by decreasing their efficiency or increasing their costs. In addition, the current regulatory environment in Myanmar means that the funding risk is relatively high in comparison to other countries (investing is deemed too risky by investors) and is to a large extent independent of BRAC’s actions, development and performance.

In spite of these challenges, BRAC has experienced steady growth as it pursued a clear strategy to continue expanding and to diversify into other development programs and new financial products. To promote financial inclusion among the disproportionately unbanked BRAC aims for its client reach to be at least 90 percent women, of which 70 percent will be in rural areas. By the end of 2021, BRAC expects to reach approximately 170,000 microfinance borrowers in 80 branches and serve a further 3,000 borrowers through its Small Enterprise Programme (SEP) which offers larger ticket individual loans to small business owners.

Microfinance+

While financial inclusion is vital in Myanmar, BRAC acknowledges that microcredit alone will not be enough to eradicate poverty, believing strongly in a holistic approach to lift the poor out of poverty. BRAC Myanmar is mindful that microfinance is not suitable for everyone and is currently exploring solutions to bring new groups into its platform. By delivering a combination of financial and non-financial services, BRAC will be able to have greater reach in Myanmar both in terms of geography and poverty reduction outcomes. For example, the 40,000 women that BRAC currently serves can benefit from diversified financial products as well as improved health and agricultural awareness. Access to certain services is expected to generate demand for others. For example, awareness building is expected to generate demand for market linkages, which BRAC Myanmar hopes to meet by developing social enterprises in the industries our clients work in.

Despite some challenges, BRAC has been able to establish operations and a strong foundation to expand both in terms of branches as well as in terms of services. Key to this throughout our development has been the application of BRAC’s institutional knowledge, drawn from past international experience, and steady incremental growth nationally.

By Sten Te Vogt (MSc student in Financial Economics from Erasmus School of Economics in Rotterdam) and Annaklara Eriksson (Lead Knowledge Management and Proposal Development, BRAC)

THE HIDDEN IMPACT OF MICROCREDIT: THREE UNDER-RECOGNIZED WAYS THE INDUSTRY CAN HELP EMERGING MARKETS

In my last post, I argued that there is a case for social investment in microcredit under the status quo, since delivering microcredit is, on average, so cheap. That discussion presumed evaluating microcredit on the terms that the industry was built on: raising the income, investment and consumption of clients. It’s on those measures that the findings of the various randomized impact evaluations have been disappointing, at least in contrast to the rhetoric that was so prevalent during the microcredit boom years.

But just because household income and consumption measures were the basis of the original microcredit theory of change doesn’t mean that, 30 years on, we can’t learn from experience and consider other ways that microcredit may have had, and continues to have, an impact. Since emotions run strong on these topics, I feel that I have to begin with a couple of pre-emptive points of clarification: a) It makes no sense to criticize the impact evaluations of microcredit, or the discussion and presentation of those evaluations, for not taking alternative channels of impact into account – these alternative channels were not the chief ways that microcredit was supposedly having an impact; and b) It’s very important to keep the word “may” in the prior sentence; these channels have not been evaluated. I am not making a claim of impact, just speculating on other plausible effects of the microcredit industry that bear considering and perhaps integrating into thinking about the cost-effectiveness of further investment in microcredit.

One of these other channels is institution building, or the creation of a significant number of reasonably well-run and governed institutions in many contexts that lack them. David Roodman lands on this channel of impact in his book (you can see a reasonable overview of the impact through institution building in this post and the various links if your copy of “Due Diligence” isn’t to hand). This isn’t a particularly new perspective, as Roodman points out, but I still think it hasn’t gotten nearly enough attention. Anyone paying attention to the world these days is getting regular reminders of the importance of institutions, how hard they are to build and how easy to tear down. If current events aren’t sufficient, you can check out Acemoglu and Robinson’s “Why Nations Fail.” You’d have a difficult time making an argument that MFIs are more extractive or less inclusive than most of the institutions in the contexts in which they operate.

The institution-building channel, though, obscures another channel that is similar but operates more at the individual level. Development economists have long recognized that lower-income countries lack mid-size companies and other organizations. More recently, economists have come to see the importance of the “technology of management.” (If you’re interested in this idea, here’s a paper that thoroughly explains and documents the idea of management as technology and one that looks at the dearth of and impact of effective management practices in small firms in developing countries.) Effectively managing even moderately complex organizations is a learned skill – and there are few ways to learn the skill in an economy that lacks dynamic mid-size formal organizations. If you consider “investability” as a reasonable proxy for “well-run” organizations, under conservative assumptions, the 500-plus microfinance institutions in that category have collectively trained more than 50,000 people in the technology of management. And that training has been delivered at zero cost from social investors’ perspective given that most of that training happens simply by being in the job. The number of managers trained will continue to grow and those managers will spread through the economies of the countries they work in, amplifying the effect of their training (and transferring their knowledge to others). If you ignored the entire customer side of microcredit, and considered the industry solely as a “job training” or “management training” intervention, it’s plausible the industry could be one of the most cost-effective such programs attempted.

A third way that MFIs may have a long-term impact is in strengthening civil society. Well-functioning countries and economies rely on demanding citizens and customers who expect to be respected and well-treated. For many borrowers, a microfinance institution is one of the first formal organizations that has treated them fairly and with respect. In other words, microfinance institutions (at least those that put customer protection and customer service principles into action) have been training borrowers to be better customers and citizens by showing them how they can and should expect to be treated by other institutions. This isn’t a novel perspective on impact either, by the way. You can see this perspective in some of the stories in “Portfolios of the Poor” where households talk about how much they value the rules-based nature of MFIs, and in many of the anthropological/sociological studies of microcredit. But it can be traced at least all the way back to the Jewish scholar Maimonides, who reasoned that going into business with the poor was superior to most forms of giving because it treated them as equals and changed the outlook of the recipient (and the giver).

None of these channels of impact are likely to yield measurable or noticeable impact in the short or even medium term. But they are worth considering as plausible additional ways that investing in microfinance institutions can have an impact, and if you find any of them at least somewhat plausible, they bolster “The Case for Social Investment in Microcredit.”

By Timothy Ogden (Managing Director, Financial Access Initiative at NYU-Wagner)

IS MICROCREDIT A VACCINE OR AN ANTIBIOTIC?

I believe there’s a strong case for social investment in microcredit, but that the best case is built on new theories of change. Historically the standard microcredit theory of change has been that many (if not most) households are eager to start their own microenterprise but are stymied by a lack of access to credit, and if credit constraints are relaxed they will be able to make profitable investments and rapidly improve their standard of living. My read of the evidence is that rather than being frustrated entrepreneurs, most people are frustrated employees (and that’s true the world over, not just in developing countries); the number of people with the proper mix of aspirations, skills and opportunities to generate meaningful profits from microenterprise is limited.

For microcredit to show an impact in terms of revenues, profits or incomes, it likely has to do much more to both target loans to the limited set of people with the requisite attributes (check out this post from Bruce Wydick) and change the contract terms so that the loans are more conducive to business investment.

But there are also other theories of change worth considering; for instance, the value of microcredit for consumption smoothing given rampant volatility in incomes and expenses. To formulate a new theory of change for microcredit, it’s useful to consider an analogy to medicine: Is microcredit a vaccine or an antibiotic? Both vaccines and antibiotics are vital tools in the fight against disease but they operate very differently, and require different delivery models and processes to have maximum effect.

Start by thinking about the nature of credit constraints in the context that you care about. One perspective is that credit constraints are pervasive – many members of the community miss opportunities to invest, or suffer from a lack of ability to buffer downturns, because they do not have access to affordable credit when needed. If you believe credit constraints are pervasive, it’s also worth considering whether credit constraints are “contagious.”

As we know, most households are enmeshed in a complex social network where families borrow from and lend to each other (or make gifts) constantly (see, of course, “Portfolios of the Poor” and the classic mobile money remittances study by Jack and Suri, for instance). These financial relationships are a vital buffer against the worst of times. But they can also limit the ability of any household in the network to accumulate enough to make productive investments, and can provide a disincentive to such investments because of the increased claims that come from the social network when such investments are made (Google “Rotten Kin Theorem”). The lack of access can therefore spread through a community and perpetually limit the entire community’s ability to invest (check out this new paper that explores this possibility through the lens of informal loans for productive investment, or the lack thereof, within a network).

If the story of pervasive and contagious credit constraints makes sense to you, it would follow that making microcredit easily available to prevent “outbreaks” of credit constraints and limit the overall effect of credit constraints on the whole community is the right strategy. If so, it would be difficult or impossible to identify who would be “infected” with a credit constraint at what point, and wouldn’t make sense to try. Better would be “vaccinating” the whole community by making credit widely available. Note that in a vaccine frame it can be very difficult to identify the value of being vaccinated at the individual level – when herd immunity is achieved the value of vaccination to an individual will appear to be zero.

On the other hand, you may believe that credit constraints are not significant to large parts of a community, perhaps because few in the community have opportunities to invest at a rate of return above the cost of credit. Or you may believe that microcredit does not sufficiently relieve the constraint except when delivered at the right dose and at the right moment. If so, microcredit is more like an antibiotic than a vaccine. Making it easily available to an entire population without diagnosing the constraint and delivering the correct dosage might be worse than doing nothing.

Think of the village markets where every stall is selling essentially the same products – making it easier for more undifferentiated vendors to enter that market is close to a zero-sum game. In such instances, microcredit would operate like an antibiotic where drug resistance can develop. Not only will it will be difficult to identify the impact of microcredit if it is widely available, but wide availability may itself limit the gains even for those for whom it is most helpful. If you find this story plausible, the most important investment in microcredit would be better diagnostic and targeting tools, even at the expense of reducing availability.

Both the vaccine and the antibiotic stories are plausible and concordant with current evidence. It’s also possible that whether microcredit should be thought of as a vaccine or antibiotic varies from context to context. Thinking through the vaccine or antibiotic frame can help social investors clarify their theory of change and guide what areas of microcredit innovation to invest in.

The bottom line is that investment in microcredit innovation is both worthwhile and necessary (see the paper for more) – but rather than just supplying more funds to the industry, social investors need to go back to the drawing board, figure out their theory of change and invest appropriately in that theory of change.

By Timothy Ogden (Managing Director, Financial Access Initiative at NYU-Wagner)

DISCOVERING THE “WHY”

Why does microfinance matter? It’s not a panacea solution. It doesn’t build global multinationals. It won’t singlehandedly dissolve poverty.

But let’s talk for a second about what it is, what it does, what it can do. Microfinance is about people. It boldly proclaims, “I see where you are today, but I believe in where you can go tomorrow.”

Hearing a woman’s story in Bangladesh a few years ago, I remember the big smile that beamed across her face as she recalled her past and how it looked so different from her present. Having nothing more than a dilapidated shelter, her husband, and her growing family 20 years earlier, this woman took out a loan from a local microfinance organization to open a small store.

Twenty years and numerous local cycles later, this woman owns two small pharmacies, employing everyone in her family, including her husband & sons – something unheard of in her culture when she first started out. She has a stable roof over her head with a latrine inside, and was even able to pay for her children to go to the university.

So why does microfinance matter? This story from Bangladesh is why microfinance matters. Because people matter. Because dignity matters.

It’s true, microfinance on its own isn’t going to drive huge increases in GDP; it won’t create hundreds of jobs per enterprise. But it can increase dignity, promote innovation, and provide economic stability for those who participate in its programs

This focus on people is what gets me excited about microfinance. Very few other development tools have the capacity to uplift men, women, and families in the way microfinance can. It doesn’t promise success, but opportunity is guaranteed. It places responsibility and creativity in the hands of loan recipients. The outcome is transformed communities.

So while microfinance may be but one tool in the development bag, it’s one my team and I are proud to support, discuss, and participate in. We get to see every day how microfinance is transforming lives, not by focusing on handouts or charity, but by challenging men and women around the globe to use business as a means to create a better life.

Opportunity. Innovation. Dignity. Hope. People. This is why microfinance matters.

A BETTER CHANGE MAKER

What do change-makers do?

We sit with the world, see it as it is, and imagine it differently.

We imagine it better.

More just and livable.

More democratic, humane, and beautiful.

We imagine projects that blue the skies, ventures that wildflower the landscapes, and start-ups that cleanse the oceans of plastics. We imagine enterprises that expand access to education, technology and markets. We imagine campaigns that unleash human potential, movements that ease suffering and experiences that deepen dignity.

And, then, we get to work.

We write down our vision, map out our theory of change and set our objectives.

We enumerate the skills and things we’re gonna need to create the change we want to see – website design, social media architecture, impact assessment framework, project management tools and many other things.

We survey what we have.

Normally, we don’t have everything we need.

No matter.

We begin anyways.

We bootstrap. We DIY. We utilize free services, piggyback on pre-existing infrastructure, and look for workarounds. We invest in learning new skills. And, of course, there will be things we need that we cannot do. Should not do. So, we harness our networks, persuade others to join us, and build a team to amplify our agency.

Together, we strategize, pitch our vision, raise funds, mobilize resources and execute.

And, when we assess our impact, more than likely, we’ll come up short.

We’ll make mistakes.

We may even fail.

And, when we do, it’ll hurt.

No matter.

We’ll learn. Iterate. Get better. Repeat.

This is the roar of our work.

This is hustle.

However, there is another aspect of our work that is often overlooked, often the most important, and often the most magnifying; namely, building deep, authentic relationships with our team and the communities with which we work.

And, how do we do that?

We ask questions of one another, listen to each other, and learn about and from one another.

It sounds simple.

It isn’t.

Why?

Well, we could talk about all of the human designed divides that separate us from one another – like race, sex, religion, language, culture, nationality, politics and more. We could also mention the constellation of unearned privileges and unwanted oppressions that go unacknowledged among us. Both are valid reasons. However, ultimately, here’s the thing that keeps us from meeting each other:

Our primal disinclination to saying “I do not know.”

Take a moment.

Try to say it.

It’s not easy.

Why?

Maybe its the insecure little kid inside of us who always wants to be right.

Who knows.

All I know is that it is important to say. Because, when we say it, we tell others that we are ready to learn. And, that is where solidarity begins.

So, how do we get to “I do not know”?

We humble ourselves.

And, how do we do that?

We can “apprentice with” the problem we want to solve by studying the interlocking system of rules, regulations, and cultural constraints in which it exists. We can study its history. And, we can investigate its political-economic context by asking: How will solving the problem disrupt current power dynamics? Who wins? Who loses? Essentially, we can choose to learn how much we do not know about the problem we want to solve.

We can also spend more time staring up at the night sky asking big questions of the universe like:

- Why am I here?

- Why is there good and bad?

- What’s next after I end?

We can surrender to its complexity.

Infinite interconnectivity.

Its vastness.

Our smallness.

Its timelessness.

Our fleeting impermanence.

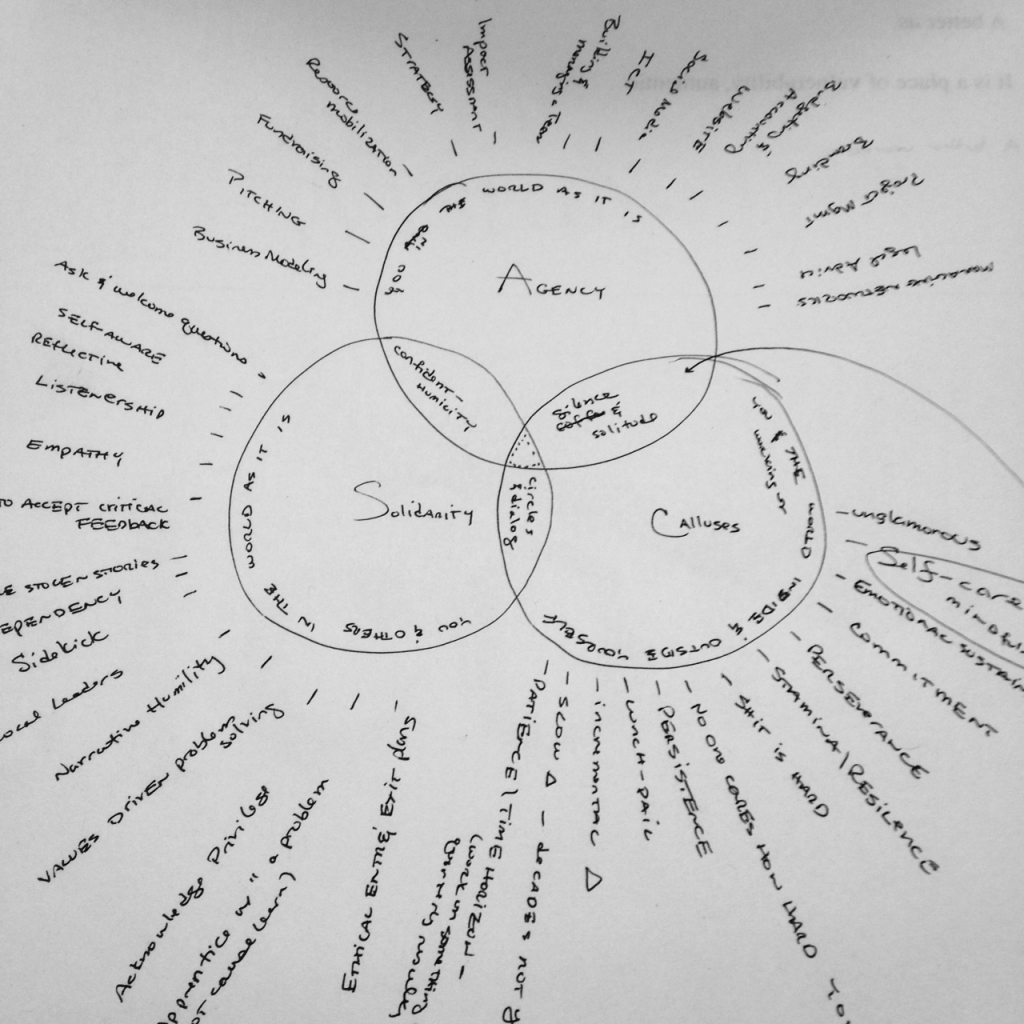

When we manage to accomplish this kind of work, we exist in the overlap between AGENCYand SOLIDARITY.

It is a place of “confident-humility”.

Here, our relationships are positioned side-by-side.

Not top down.

Here, we do things with each other.

Not for each other.

But, alas, it is hard to stay here.

AGENCY and SOLIDARITY are elusive.

We never have a permanent grip on either of them.

Sometimes we let others take them away from us.

But, let’s be honest.

Mostly, we just give them away.

Our fears erode our confidence. Our self-doubt dissipates our voice. And, some days our insecurities are so sharp that we don’t want to know what we do not know. We want to generalize, categorize, and put people in their “proper” place. We want to infuse those around us with simple narratives and retreat into a I know, I’m right, me first, I want, gimme-mine, take-take-take, self-centered world of isolation.

We have to earn AGENCY and SOLIDARITY anew.

Each and every day.

All day.

Until the end of the day.

And, how do we do that?

We go off to a sacred space of solitude, sit in silence, and assess our lifestyle by:

- Critically reflecting upon the human constructs we have internalized.

- Measuring the depth of our submersion into the dominant consumerist culture.

- Questioning our past and reconsidering our upbringing.

And, since we humans are largely at the mercy of what we do not know about ourselves, we go into the deepest, darkest, dampest wilderness of our souls to sit with our demons and ask them “Where does it hurt?”

Yet, this unwinding of our humanity is too big of a job to be done in solitude. We need others. So, we seek out others, gather in circles together, and do it together for each other through dialogue.

We share our hopes. We share our fears. We expose our weaknesses. And, as you can imagine, this takes a lot of trust. But, within this vivacious circle of humanity lies an immense possibility. Namely, that if we remain present for each other and give of ourselves to each other, we may get to know ourselves better, get closer to the “why” of our existence and maybe help each other in the same way.

Together, we can remind each other that the world as we know it – inside and outside of ourselves – is not fixed. It is malleable. And, we are agents of change.

This – all of it – is what change-makers do.

This is the work.

It is not easy.

Most of it is unglamorous.

And, all of it is necessary.

Making change is a roll-up-your-sleeves-lunch-pail-labor-of-love that gives us calluses.

They grow layer by layer each and every day. They harden. They hurt. But, they are a testament to our patience, persistence and commitment to the work.

It is at the intersection of AGENCY, SOLIDARITY and CALLUSES that a better change-maker exists.

My notes…

THE JOURNEY OF A MICROFINANCE VETERAN: BRAC’S MD. SHAHIDULLAH

How does one sum up half a lifetime of work to promote financial inclusion for the poor? A career that spans over 24 years, starting from introducing microfinance at the grassroots to being the digital innovation lead in a multinational microfinance provider, to initiating microfinance in a new, and at times, frightening country – Mr ShahidUllah’s story depicts an adventure seeker with unrelenting willpower to achieve his mission.

“I joined BRAC in the year 1993. I was a fresh graduate and started working in a large garment conglomerate. But I was bored after a few months with the routine work and when I saw a job circular advertising a Program Officer position at BRAC I applied instinctively, without even knowing anything about my role and future. Everyone discouraged it but I persisted”, Mr ShahidUllah’s simple confession. And this humble persistence is evident throughout his career at BRAC.

ShahidUllah was commissioned to the field and tasked with the responsibility to bring a new community under the benefit of financial services. Together with his team, he went door to door, developed groups of women borrowers, determined participant selection criteria and oriented the participants of BRAC on how to use microfinance. He became the manager of that branch within a year and steadily ascended to becomea Regional Coordinator of the Microfinance program by 1999. Apart from supervising staff and maintaining a growing portfolio of borrowers and savers, ShahidUllah also monitored activities of other BRAC programs in that region. In 2003, he was selected to help BRAC set up its first international venture – a microfinance programme in Afghanistan.

“When I went to Afghanistan in 2003, the country was still trying to rise from the devastation of decades of war. There wasa very limited formal banking system, very limited infrastructure, the concept of microfinance was new, and so we faced a lot of challenges. The most difficult part was to educate the local managers and employees who would become frontline staff about their duties.They had suffered years of trauma and had very limited work experience and management skills. We had to provide constant training and motivation to the staff. ShahidUllah soon took over management of the branches within his province – setting yearly targets, budgeting, cost management, headquarter coordination as well as maintaining liaison with the external stakeholders such as the district government representatives. The results were promising but his stay in Afghanistan was short-lived due to an unexpected incident.

“It was the end of the month and I was out to disburse staff salaries on my motorbike. I was driving through the rough terrain, coming back from the farthest branch, when I suddenly lost control and fell. I was so surprised by the incident that I could not properly register what went wrong. I rolled down from the road and landed on the dirt a few meters below. I looked around, perplexed, trying to figure out what happened, when I noticed a man carrying a rifle slowly walking towards me from the other side of the road. I instantly closed my eyes and awaited my fate. After a while, I felt him removing the bag from my shoulders and then he left. Slowly, I came to my senses and attempted to move towards my bike. But I was met with excruciating pain. It was then when I realised that I was shot in my right hand and leg. I somehow crawled towards my bike and waited for a passerby. Luckily, a police patrol arrived a few minutes later and they took me to the nearest hospital. I was lucky that my wounds were not fatal. With the timely assistance from the head office and my colleagues in Afghanistan, I was released after a few days and returned to Bangladesh”.

After two years of an eventful stay in Afghanistan, in 2006 ShahidUllah returned to Dhaka. Within a couple of yearshe had a new mission: introduce digital financial services to Bangladesh. ShahidUllah was an integral part of the team who piloted and helped scaleup bKkash – BRAC Bank’s mobile money platform, before it revolutionised how the the country conducted financial transactions, and became the largest mobile money provider in the world (in terms of clients and transactions). Now, millions of rural and urban population of the country previously excluded from the financial systemare abler to transfer and deposit money via mobile phone.